Joel Mokyr and the 2025 Nobel Prize

This was first published at Fusion and I am very grateful to Sam Goldman for comments

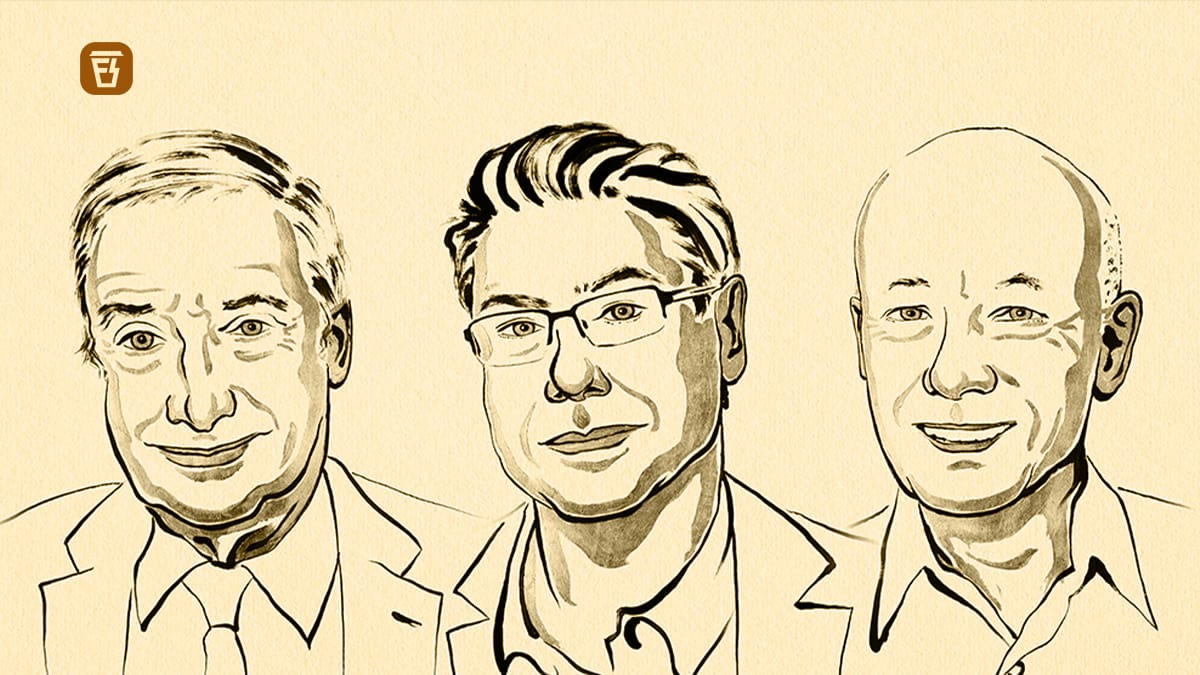

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded for explaining innovation-driven economic growth. Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt were pioneers in endogenous growth theory and many would assume that they missed their moment when Paul Romer won in 2018. Now their seminal contributions in growth theory have been paired with Joel Mokyr’s insights into the historical process of economic growth and innovation. It is Mokyr’s work that I want to focus on here.

Mokyr’s earliest work (including a formal model published in Explorations in Economic History in 1976) was focused on issues of economic growth. But until he wrote The Lever of Riches in 1990, Mokyr was best-known for his work on the Irish famine of the mid-19th century. The Lever of Riches, however, was a blockbuster. It is a testament to the book’s impact and longevity that it is still on many undergraduate reading lists today (including my own).

From The Lever of Riches onwards, Mokyr’s work has not just been focused on growth but specifically on the question of innovation. Innovation has two components: the first is pure discovery, and is traditionally the subject matter of the history of science. The second is the process of bringing a discovery to market and turning it into a profitable part of a business. Mokyr’s work seeks to explain both why Europe became an intellectual hub of discovery after around 1500 and why and how this eventually translated into modern economic growth in the 19th century.

In that book, Mokyr distinguished between macro-inventions and micro-inventions. By the former, he meant what we often call general purpose technologies such as the printing press or the internet. Macro-inventions have the potential to be transformative but it often take many decades for their full impact to be felt. Moreover, macro-inventions are potentially sterile unless complemented by a stream of micro-inventions, small improvements and cost-savings that improve the initial technology and allow it to be disseminated on a broad basis. For example, the macro-inventions of the internal combustion engine and the automobile required a host of complementary improvements (such as rubber tires) to ultimately bring about the transformation in transportation that took place by the early 20th century.

Mokyr’s insight was that a lone genius inventor such as a Leonardo da Vinci could not on his own have much impact on the history of technology and growth. I recall a British TV documentary from the 2000s where scientists established that many of Leonardo’s inventions such as his parachute and helicopter were feasible in design. But lacking either supporting micro-inventions or craftsmen and mechanics capable of implementing his ideas, these insights were neglected by Leonardo’s contemporaries.

The series of books Mokyr has published since iterated on this topic, providing novel insights into the process of innovation. An important difference between Mokyr’s work on these topics and those of most historians is that he continuously relates discoveries in science and technological breakthroughs to the overall problem of economic growth. He was interested in explaining why economic growth was largely stagnant for so many centuries before the Industrial Revolution.

These books have fundamentally reshaped how economic historians think about the origins of sustained economic growth. When I reviewed his 2016 book A Culture of Growth, I observed that while in previous work,

“Mokyr advanced what one could consider as cultural arguments for the rise of, not only inventors and innovators, but also a workforce made up of tinkerers and ‘improvers’ in eighteenth century England. But in those books, he shied away from investigating in full the forces that help to give rise to such culture of practical innovation and improvement.”

In A Culture of Growth, Mokyr focused explicitly on culture. At the time, I noted that this was a recognition that culture had arrived as an important and legitimate concept in discussions of economic growth. Jared Rubin and I focus extensively on these arguments in our book, How the World Became Rich.

But here I want to focus on one important part of Mokyr’s argument, an aspect that has been picked up by researchers in the field but perhaps has not yet penetrated beyond that: the complementarity of institutional and cultural explanations for economic growth.

Many books pose a dichotomy between different explanations of what Deirdre McCloskey calls the Great Enrichment or the origins of sustained economic growth: it is either geography and sheer “luck,” or exploitation; or it is all institutions; or all cultural values. As Rubin and I discuss, however, it is an obvious mistake to assert that these factors operated in isolation of one another. Any plausible explanation of the origins of sustained economic growth has to take into account their interaction.

This is something that Mokyr has been stressing in his work for at least two decades. In particular, he draws attention to what he calls a “meta-institution”: the Republic of Letters.

Beginning in the 16th century but really getting going after 1600, Mokyr discusses the emergence of a transnational and later trans-religious community of scholars, which referred to itself as the Respublica Literaria. This circle of scholars drew its membership from scientists, physicians, philosophers, and mathematicians, as well as theologians, astrologers, and mystical and occultist writers.

Mokyr’s emphasis on the shared beliefs and values of this educated and polyglot community is an argument for the importance of cultural values. These thinkers promoted innovation. In contrast to their medieval predecessors, they did not revere the ideas of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Galen or engage in what Carl Becker called “ancestor worship”. Rather, their behavior was competitive (sometimes unscrupulously so) as they sought to uncover the secrets of nature.

But it is also an argument for the importance of institutions. This group of scholars itself functioned as an informal international network and as well as distributing new ideas and findings, it generated insights that incentivize further innovation.

By the late 17th century something resembling “refereed” scientific periodicals began to emerge, such as the Transactions of the Royal Society. Improvements in transportation made it possible for books to be distributed more widely. The physical infrastructure supporting this virtual community included universities (especially Padua, Paris, and Leyden) but these were less important than the more informal academies and scientific societies.

Institutional infrastructure was critical. Mokyr draws attention to the importance of the postal system. The origins of a European postal system lie in the 15th century as the de Tasso family began organizing a postal network in Italy. This expanded into the Holy Roman Empire in the 16th century. By the 17th century, all of Europe was linked together by a network that enabled continuous and reliable correspondence between scholars living in different countries, a necessary precondition for the emergence of the Republic of Letters.

Institutions also matter at a higher level. All of this took place against a backdrop of a competitive and fragmented state system. As Mokyr contends, and as Noel Johnson and I also argued in Persecution and Toleration, this made it very difficult for any one state or ruler to suppress new knowledge or new ideas. Members of the Republic of Letters, Mokyr documents, used foreign publishers to circumvent censorship. In extreme cases, footloose members moved from one nation to another and played one power against another. The combination of political fragmentation and competition between dynasties, polities, and different religions made coordination by reactionary powers almost impossible. By the 18th century, troublesome books were still being burned in Western Europe, but thinkers were not being physically coerced.

This set of arguments nicely illustrates the interplay between institutional and political factors and cultural factors and shows how difficult it can be to disentangle them cleanly.

These arguments also slot in nicely to other explanations of the origins of growth which emphasize other factors such as political institutions or skills and human capital, which Mokyr also stresses in other research (for example, his work on millwrights, and skilled workers in general). Indeed, in his work from A Lever of Riches onward, Mokyr gradually constructed a rich framework which weaves together many such factors into a coherent account of how sustained growth emerged.

Throughout his research, Mokyr has focused on addressing questions about the timing and location of the Industrial Revolution that economic historians have long puzzled over. Specifically, why did it take place in Britain and not in another part of Europe or the world? And why did it take place in the 18thcentury and not earlier or later?

Drawing on this larger body of work, one can reconstruct a narrative that begins by explaining the origins and success of the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries, a pan-European phenomenon which provided the vitally important propositional knowledge that future technological developments would eventually come to build upon but which itself did not translate directly into faster economic growth.

Mokyr then traces the application of selected scientific principles into industry itself in the 18th century. This was a development that Mokyr terms the Industrial Enlightenment. Unlike the Scientific Revolution, it was predominantly a British phenomenon. It was based around tea and coffee shops, where scientists, entrepreneurs and skilled artisans interacted and shared ideas. And of course, institutional factors were crucial: political stability, integrated markets, and religious toleration were preconditions for this Industrial Enlightenment. These all provided background conditions for the Industrial Revolution itself.

But Mokyr’s narrative does not stop there. His work has also considered the application of modern science after 1850 and it contains insights that have direct relevance for today. At a time when there seems to be a growing backlash against technological progress in many parts of the world and on both sides of the political spectrum, this is a Nobel Prize that acknowledges the importance of innovation and technology. Mokyr’s particular contribution has been to lay out in great detail how innovation took root in Western Europe in the early modern period. While many are seeking to restrain innovation in the name of various political causes, Mokyr reminds us of how much we have to gain through free exchange and a competitive marketplace for ideas. By giving the prize to Mokyr alongside Aghion and Howitt, the Nobel committee have rewarded research that points to the deep historical origins of modern prosperity.

Though I do not agree with his theory in the cause of the Industrial Revolution, I am very excited about Mokyr being awarded the Nobel Prize. It was greatly deserved.

Excellent post. I wish I had had it when I was writing my WSJ piece on the award.