Masters of the Air

The Economics of Bombing in World War 2

Our current favorite show is Apple TV’s Masters of the Air, created by the same team as Band of Brothers and the Pacific. It is a remarkably realistic and compelling depiction of the American 8th Air Force and 100th bomber group in World War 2. The underlying stories are based on Donald Miller’s book of the same name. The show rightly focuses on the tremendous risks that bombers faced - serving in the 8th Air Force’s was the 3rd most dangerous combat branch in the entire war after being a Japanese kamikaze pilot or in a German U-boat.

But how effective was bombing Germany was in terms of shortening the war? The scholarly consensus downplayed the effectiveness of strategic bombing. This is reflected in best documentary series on the war: The World at War (1973).

Episode 3 of Masters of the Air captures the iconic raid on Schweinfurt and Regensburg in June 1943 (and the second raid on Schweinfurt in October 1943). This destroyed 50% of ball-bearing equipment. But the losses were huge: 24 flying fortresses lost on the attack on Schweinfurt and 36 on Regensburg or 16% of the combined force. In the show, we see Lt. Biddick, played by Barry Keoghan, die in this raid.

But what does the latest scholarly work say about the impact of 8th Air Force’s strategic bombing campaign? And what does the economic approach to war tell us?

The Myth of Decisive Battle

Before we get to the value of the economic approach to war, a myth needs to be laid to rest. That is the myth of the decisive battle.

Traditional scholarship centers decisive battles. We’re told that Stalingrad or Kursk or El Alamein (I guess only by Brits) were the decisive battles of World War II. The decisive battle is appealing because it condenses the horrors of war into a single moment of decision. Modern generals still study Cannae in the hope of replicating a battle of annihilation (though of course, Cannae was not decisive).

Stalingrad did not destroy the offensive capabilities of the Wehrmacht. So why is it seen as decisive? Perhaps because of the losses sustained. The 6th Army was all but wiped out, as was the 4th Panzer army (total Axis losses were in the 800k-1 million range though many of these were Romanian and Italian allies). 900 fighter aircraft and around 1500 tanks were destroyed.

Is that enough to make a battle “decisive”? The Battle of Kiev in 1941 was seen as decisive at the time. Hitler called it the greatest battle in history thus far. Soviet losses were in the range of 700k. But Kiev didn’t prove to be a decisive because the Soviet Union could replenish its losses.

Cathal Nolan argues in The Allure of Battle (one of my favorite books of 2017) that there were no decisive battles in World War 2. Stalin was closer to being correct when he noted that “The war will be won by whichever side produces the most motors.” From this perspective, German military capability was:

“. . . reduced by local German victories as much as by defeats. That is the nature of matériel war. No one battle or named defeat was decisive in a war-winning sense: not Stalingrad, El Alamein or Bizerta, not even Kursk. Instead, each great battle accelerated the wearing out of Germany’s armed forces and reserves, steepening the arc of attrition until all strategic initiative shifted to the Allies, inside Soviet territory then in eastern Europe, at sea and in the air.” (Nolan, 2017)

This brings us back to the value of strategic bombing and the economic approach to war.

The Economic Approach to War

By the economic approach to war, I refer to quantitative work that not only emphasizes the importance of resources and attrition in determining war outcomes but is attuned to the concept of opportunity cost.

Conventional wisdom has it that Germany lost World War 2 on the Eastern front. Certainly, the bulk of German manpower losses were sustained fighting the Soviet Union. However, a lack of manpower was not the reason Germany lost.

Philip’s O’Brien in How the War Was Won (2015) demonstrates the importance of airpower and attrition in Allied victory. O’Brien notes that up until 1944, German manpower losses were manageable and running below their World War 1 rates. Until July 1944, far more young German men were turning 18 and entering the armed forces than were “exiting’ as causalities. This changed dramatically once the Western allies achieved air superiority following D-Day. All

O’Brien’s assessment about the paramount importance of airpower was echoed by German army chief Alfred Jodl after the war.

“Not taking into consideration the Russian air force, which was of no great importance, I would say in general that in the end the winning of the complete air superiority in the whole area of the war has altogether decided the war. I would go as far as to say that our power on the land was numerically and, from the point of view of armament, sufficiently strong, if not to win, at least to hold our own on all fronts, if our air force had kept up on the same level.”

General Alfred Jodl (quoted in O’Brien, 2015, p 373)

Why was airpower so important and how does relate to Masters of the Air? O’Brien emphasizes three factors:

Pre-battle destruction

Pre-production destruction

The control of mobility

Battle and pre-battle destruction

If we accept that what ultimately mattered was the destruction of airplanes, tanks and artillery i.e. the means of war, then it doesn’t matter where they are destroyed. Indeed it is typically much cheaper to destroy a plan on the ground than in a dog fight.

From 1943 onwards, the allied bombing campaign began to make its mark on German production numbers. The Regensburg raid depicted in Masters of the Air is widely seen as a failure, but O’Brien argues that this assessment should be revised:

In the end, the 100th suffered more than any other 8th Air Force unit during the Regensburg raid, losing nine of its twenty-one B-17s. This was an unsustainable casualty rate, and it is one of the reasons that the Anglo-American strategic air offensive of 1943 is almost universally seen as a failure. And yet, for all its heavy losses, this one raid on Regensburg destroyed far more aircraft than the Germans lost during the Battle of Kursk, perhaps more than they lost on the Eastern Front during all of the summer of 1943. From the point of view of the ultimate destruction of German power, the strategic air campaign was a necessary failure.

Strategic bombing in 1943 did not live up to the overblown expectations of the American “air mafia” and the RAF commander in chief Arthur “Bomber” Harris. Losses averaged over 8% - in the Regensburg/Schweinfurt attack they were 26% - compared to the 4% maximum loss rates promised by the 8th’s air chiefs.

The Allied commanders were slow in taking into account German improvements in air defense, and the vulnerability of unescorted bombers, even those as heavily armed as the B17s and B24s. The British and Americans failed to coordinate their attacks, rarely choosing the same cities or locations to target. Estimates of the damage they were causing were wildly over optimistic. Attacks on submarine pens proved to be a waste. Nonetheless, O’Brien notes that even in 1943 Allied bombing decisively affected German production decisions and shaped the Luftwaffe’s choice of strategic priorities.

Critically, planes were withdrawn from the Eastern Front where they could have played a crucial role. As this Figure, from O’Brien (p. 219), indicates by late 1943, 70% of German fighters were for home defense. Moreover, the fighters left on the Eastern Front tended to be older models.

Between July to November 1943, 42% of German aircraft losses were sustained in defense of the Reich relative to 28% on the Eastern front. Allied attacks over German airspace made it increasingly difficult for German pilots to train. By late 1943, Allied pilots typically had twice the training of their German counterparts.

In short, one cannot simply ascertain that the Allied bombing campaign in 1943 was a failure from the naked observation that German war production did not fall as hoped (it increased). Given the currently available data, we cannot recover an estimate of the true causal impact of the bombing. But as O’Brien documents, it had repercussions across the German economy.

Pre-production destruction

Destroying German aircraft before they took off was obviously more cost-effective than shooting them down once airborne. And non-operational German aircraft losses soared in 1943. But the Allied bombing also reduced the amount of resources available for war production.

it would be conservative to say that the total number of German aircraft, mostly fighters, destroyed before production because of factory destruction, relocation and aluminum losses in 1943 was somewhere between five and six thousand . . . The USSBS estimated that between July 1943 and December 1944, German aircraft production was reduced by 18,492 units because of strategic bombing, of which 14,353 were fighters (O’Brien, 2015, p.298).

Industrial workers and resources were pulled from other occupations into protecting German cities against air assault. 28,000 workers were involved in building Hitler a bomb proof bunker. Taking into account these diverted resources, O’Brien concludes that as early as 1943 “the Combined Bomber Offensive was tying down or destroying more production than any part of the land war, the Eastern Front included” (p 315).

Hitler said that who controls oil, wins the war. From June 1944 German supplies of aviation fuel collapsed. This was largely due to the Allied bombing campaign. By the time the Allies had captured the oil fields in Romania, the damage to German industry had already been done. Hundreds of thousands of workers were diverted to repairing oil facilities. Workers who could otherwise have been employed in armaments production.

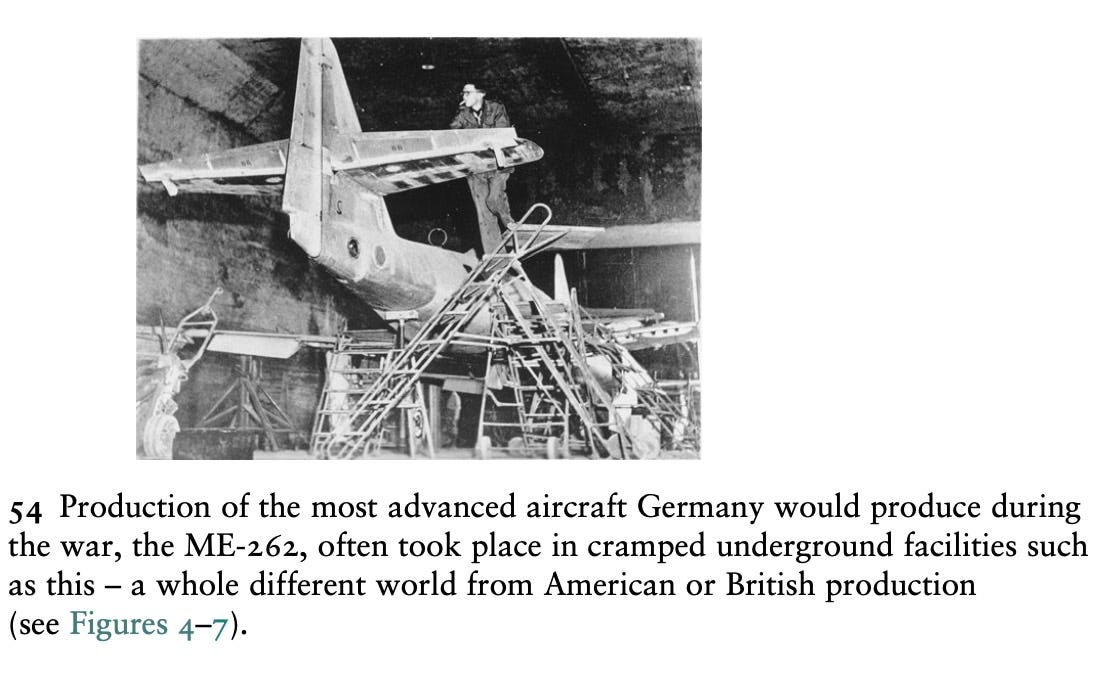

Economic analysis often reveals hidden costs and benefits. One hidden cost that the Allied bombing campaign imposed on Germany was the dispersal of production. Whereas American planes could be produced in spacious factories and hangars designed to exploit economies of scale, German production often had to take place underground.

In contrast here is a picture of the Boeing Wichita Plant where B29s were produced.

Unsurprisingly, given America’s prewar lead in manufacturing, no other protagonist approached US production levels and productivity. Germany and America employed approximately the same number of workers in aircraft production but:

the Germans suffered through great inefficiencies – many owing to the pressures of building aircraft under the threat of air attack. The physical process of dispersing production to the east itself caused production declines just because of transportation. These structured to build bombers had to be completely reconfigured to build fighters, losing a great deal of their productivity while the process was ongoing (p 329).

The Control of Mobility

Finally, allied bombing gave them control of mobility. And mobility - that is, the ability to move military resources to their highest value use - is the essence of strategy. Allied bombing made it increasingly costly for the Germans to do this. Air superiority meant that while German infantry could defend fixed positions, they could not easily retreat or reorganize.

By bombing transport links within the Reich, the allies cut off industrial centers from supplies of raw materials, notably oil and coal. Coal production in the Ruhr collapsed in 1944. The lack of coal had a knock-on effect on iron and steel production.

Both Japanese and German armaments construction went into a terminal decline in the summer of 1944, when their empires still possessed all the raw materials needed to keep production rising. One of the main reasons for this was the inability of both to transport raw materials from their sources to the refining factories, and then from those factories to the place of finished munitions production (p. 482)

With the loss of mobility and tactical advantages that entailed, Wehrmacht losses spiked. In July and August of 1944 total deaths in the German armed forces equalled the total number of deaths in the entirety 1942. From this point, German defeat was inevitable.

All of this is to say that the effects on production of Allied bombing in World War 2 were anything but a failure. The collapse in morale envision by Bomber Harris and others did not happen. Nonetheless, there is intriguing new research by Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova and Hans-Jochim Voth suggesting that the allied bombing campaign encouraged resistance to the Nazis. But I will leave that for another blogpost.

Masters of the Air does a fantastic job of depicting the sacrifices made by the men of the 8th Air Force and their courage under fire. But the economic approach to warfare adds to our understanding of just how critical their contribution was.

While the Bomber Barons exaggerate their results the bombing campaign clearly did contribute (though I need to dig in and see if anyone has measured the resources put into our bombing effort against the resulting destruction of German capability). One added element to the Allied effort was the addition of longrange fighter escorts to protect the bombers both out and back - and then we started freeing up the fighters to independently attack targets of opportunity such as German airfields and road and rail targets. Also one response to the threat of the jet engined Me-262 was to focus on catching it during its take off and landing runs. By 1945, the first Allied pilot to spot one would generally broadcast the warning "jet, jet, jet!" and every Allied fighter would head for the nearest German airfield with a concrete runway (essential for the Me-262s) and wait for the jets to show up so the Allied pilots could catch it trying to land or catch others trying to take off.