An Idiosyncratic Economic History Course

Part 1: 1870 - 1923

I’ve just finished teaching Econ 460 for the first time. This is a seminar style course for advanced undergraduates at GMU It is labelled as a Senior Seminar in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics (PPE). But in practice, the instructor has the freedom to choose the subject matter. I choose to teach an idiosyncratic course on 20th century Economic History.

Here is the syllabus. Some highlights are below.

The course was (I think!) a success. While I’ve taught economic history for more than a decade, my class has always focused on pre-20th century history. Basically, I stop around 1870 with the Second Industrial Revolution underway. So this was my first foray into teaching more more modern topics like World War 1 and World War 2. And it was the first time teaching the Great Depression since I was a grad student (teaching it admit the Great Recession).

I didn’t use a textbook. Had it been out, I would have assigned Christopher Meissner’s One From the Many as a background text. The standards of a modern undergrad class also meant that I wasn’t able to assign the kind of voluminous readings that used to be assigned to me as a student. This meant that I used the lectures to summarize classic works by Peter Temin, Barry Eichengreen, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, Bob Allen, Paul Gregory, Kevin O’Rourke and Jeffrey Williamson and others to supplement the core readings.

As the class was nominally a PPE class, I included background on the history of ideas. My colleague Larry White’s book, The Clash of Economic Ideas, was on the reading list for this reason, though in practice I drew on a wide range of books including Brian Snowden and Howard Vane’s Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development and Current State, which is very much as “schools of thought” book, but is a great resource if one wants a more historical approach to macroeconomics.

In this post I’ll summarize the first couple of weeks of the class. A second post will cover the rest.

How the World Became Rich was essential background material for the course. It provided the context for the students to understand the rapid spread of modern growth after 1870. The other main reading was Brad deLong’s Slouching Towards Utopia. While I have some substantive disagreements with bits of this book, overall it did a great job of providing a narrative economic history of the entire period. DeLong’s framing of Hayek versus Polanyi provided a good starting point for class discussion.

For the first half of the semester focused on 1870-1945 - taking DeLong’s definition of the long 20th century seriously. The first two weeks of class covered 1870-1914, the first age of globalization. We considered the role of the telegraph and the steamship in opening up the world. We ask what impact failing transport and trade costs had on the allocation of economic activity?

The first age of globalization brought sustained economic growth to the West but also saw global inequalities widen. In class we examined the institutions, like the international gold standard, that supported it. We look at the dark side in the form of colonization. And we considered the intellectual ferment of the period and new ideologies like socialism emerged and classical liberalism waned.

World War 1 destroyed the first age of globalization. But what caused World War 1? Important factors include the entangled military alliances that divided Europe into two rival camps, the imperialist rivalries between the Great Powers (particularly Germany and Great Britain), German nationalism and militarism, political instability in the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian Empires, and the Balkan crises that escalated tensions in the region. We weighed the evidence as best we could before diving into the economics of the war itself.

As in my earlier post on Masters of the Air, I took a very economics-focused perspective in my lectures to studying the war itself.

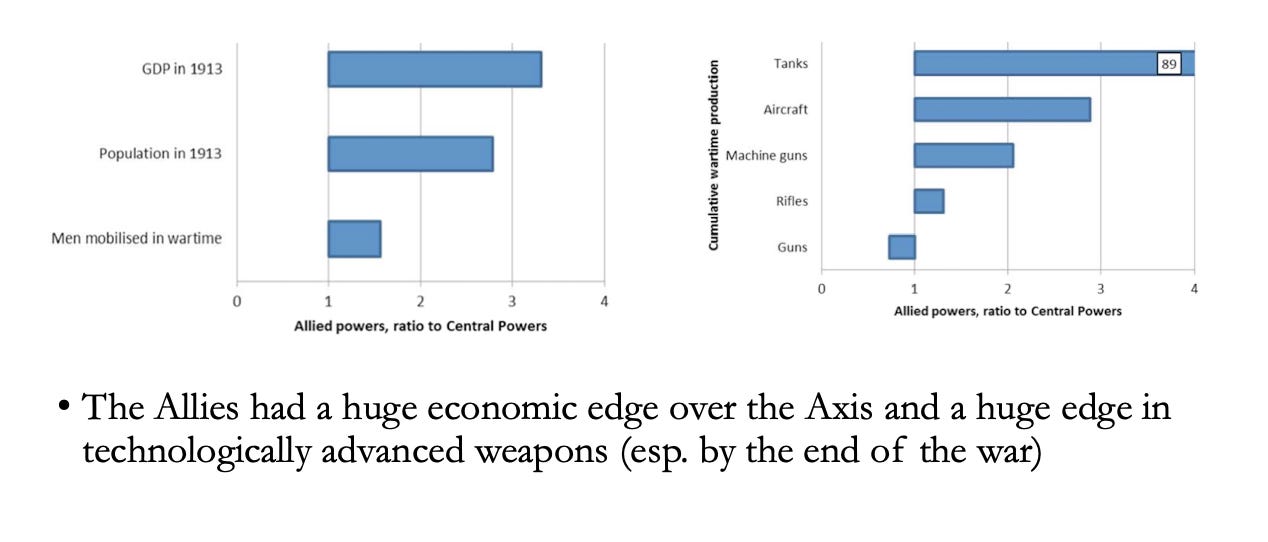

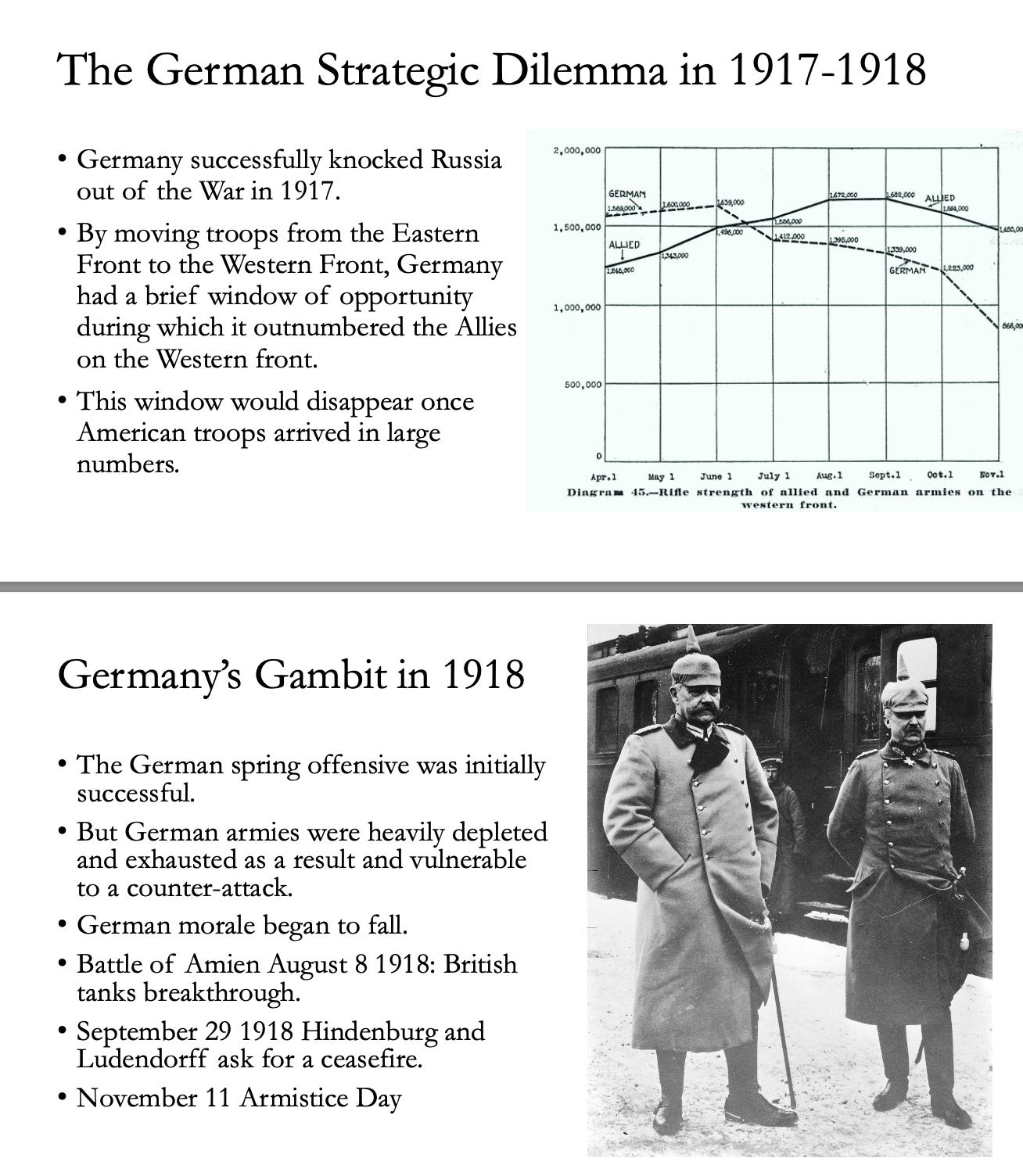

From this economic perspective, once Germany had failed to win a decisive short war in 1914, Allied victory was always more likely. And the decisive edge the Allies had over the Axes only grew over time, especially following American entry in 1917.

World War 1, however, just set up the world for another crisis within 20 years. The Treaty of Versailles is of course blamed for this.

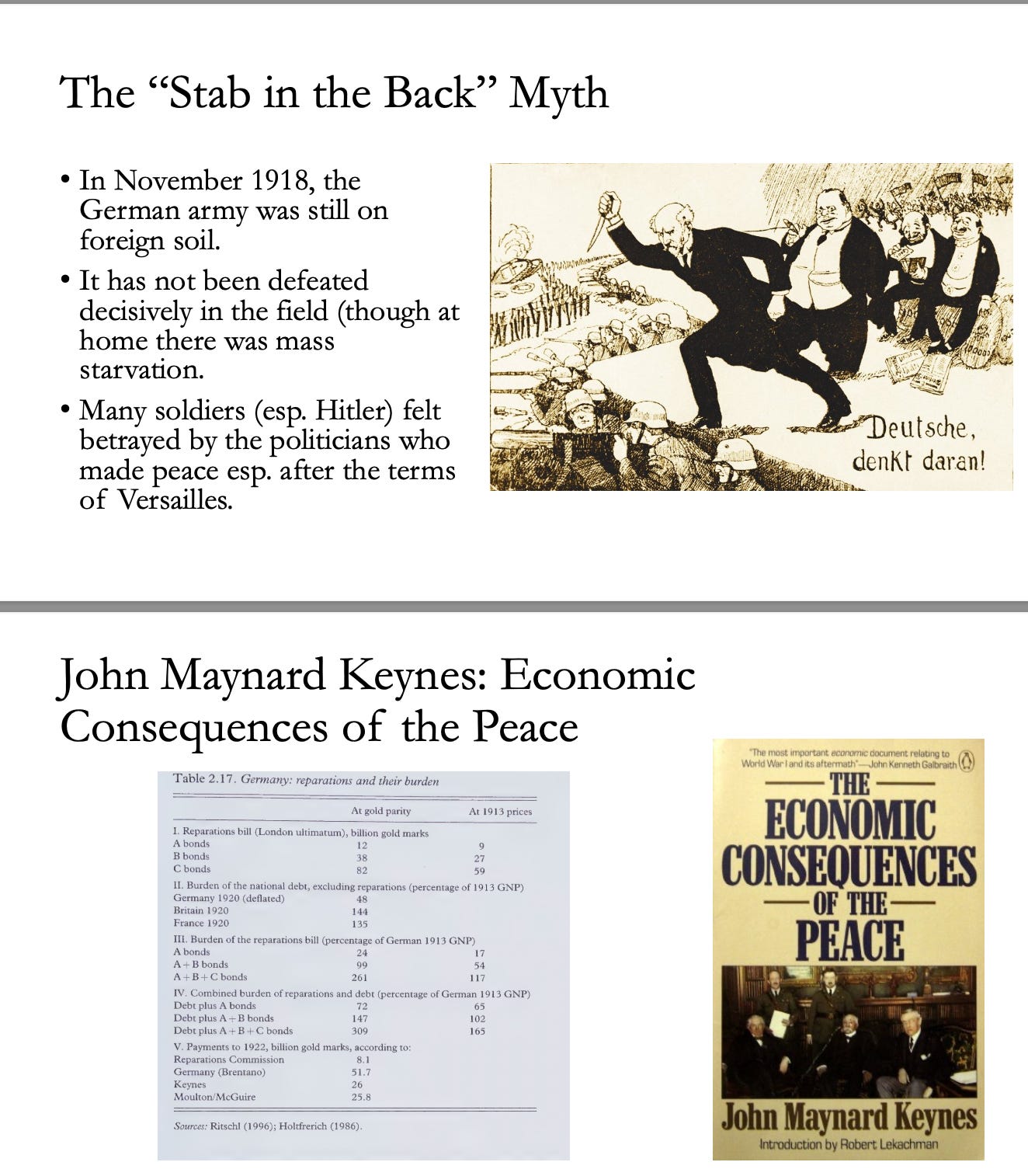

Here we covered Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points and different perspectives on the Treaty of Versailles. I’m skeptical that the Treaty of Versailles was an especially harsh treaty. And I share Tyler Cowen’s views that The Economic Consequences of the Peace is overrated. But perceptions are often what matters most in politics.

Delong in Slouching Towards Utopia does a great job of linking wartime inflation in Germany and Austria-Hungary with the hyperinflations of the 1920s. The model he summarizes is the fiscal theory of the price level.

In Germany, opposition to reparations meant that it was politically expedient for policymakers to print money rather than raise taxes to pay Germany’s debts. The attempts to rebuild Germany’s economy following the resulting hyperinflation through the Dawes Plan and the international failure to properly restore the pre-1914 Gold Standard would expose the world to the Great Depression.

Before we examined the Great Depression, however, the class pivoted back to study the rise of socialism in the late 19th century. My next post will pick up the story there.

When putting this together did you come across any comparative studies on the economic impact of the French 1871 indemnity (which was iirc relatively greater) with 1919 Germany?