Do Individuals Matter in Institutional Economic History?

Together with Desiree Desierto, I recently completed a chapter on Institutional Change for the Handbook of New Institutional Economics (SSRN).

Institutional analysis typically eschews emphasis on individuals. A development like the demise of serfdom in late 14th and early 15th century England did not hinge on the actions or ideas of a single peasant or lord. The Industrial Revolution would have taken place even if we removed a James Watt or Richard Arkwright from history. The underlying premise of institutional analysis is that there are deeper, structural factors that tend to matter more than any one individual.

Neglect of important individuals is not unique to economic history. Among academics, the Great Man Theory of History died a long time ago. Even invoking it risks cliche.

But there do seem to be individuals who have a huge impact on history. Alexander the Great is an obvious example. Had his father Philip lived, he would have invaded the Persian Empire. But all the evidence suggests, that he would have been satisfied with “liberating” the Greek cities of Anatolia. After several battlefield successes, he would likely have accepted a large payment from the Persian emperor to withdraw and enjoy his hegemony over the Greek states. Alexander’s unique personality traits do seem responsible for the extension of a Hellenistic empire all of the way to India.

Martin Luther: A Man Who Changed History

Another individual who had a similarly decisive impact was Martin Luther. I recently enjoyed listening to The Rest is History’s series of podcasts on Luther. Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook are in little doubt that Luther’s impact was decisive and that Luther was among the most important individuals in history. Episode 1 is subtitled: “The man who changed history“. Top 5 is their assessment: “Bigger than Marx”.

Luther scholars tend to be more cautious. They refrain from strong counterfactual claims (such as “no Luther, no Reformation”). And, of course, the question of whether any individual is truly decisive in that sense is probably impossible to answer. But we do have the tools and evidence to evaluate the evidence for Luther’s impact in more detail.

We argue in our chapter that individuals can have a role in institutional analysis.1 Or at least, we propose one way of thinking about their influence analytically. We propose that individuals influence institutional change in two distinct ways: (1) by exogenously shifting some parameters in society i.e. technology or preferences; (2) by solving coordination problems. Luther is notable because he clearly did both things.

Let’s briefly talk about (1), though the majority of this post will be occupied with (2). Luther was professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg. As historians like Peter Marshall emphasize, this was not a prestigious university; nor was Luther prior to 1517 a famous or well-published theologian. But Luther was in a sense the “right man” at the right time (or perhaps wrong man, at the wrong time depending on your theological point of view). He entered the intellectual fray at the same time as a tremendous controversy about the sale of indulgences was breaking out. And his writings certainly caused people to reevaluate their religious beliefs.

Johan Tetzel had been commissioned to sell indulgences by Albrecht, Archbishop of Maniz and Magdeburg. As Marshall describes it:

“Albrecht’s court theologians drew up an Instructio Summaria (Summary Instruction) with guidelines to preachers on how to present it most effectively. This confirmed that the new issue superseded and invalidated all previous grants of indulgence for the next eight years—a source of understandable annoyance to people who had bought earlier ones in literal good faith. Generally, the Instructio took a maximalist line on the indulgence’s power and efficacy. Most notoriously, it suggested that people buying the indulgence on behalf of the dead had no need to make confession or exhibit contrition, as its effectiveness depended on ‘the love in which the deceased died, and the contributions of the living’.” (Marshall, 2017, p 29)

This according to Marshall was at the very least questionable, and Tetzel may have gone further using the slogan: ‘as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, at once the soul to heaven springs.’

It was in this perhaps only in this already charged and febrile atmosphere that Luther’s writings could have had the impact that they did. Historians emphasize that in 1517 Luther’s positions were mostly orthodox. He wished to limit not abolish indulgences and accepted the concept of purgatory. But his opposition to the practices of indulgence and the printing of his 95-theses made him a celebrity.

Luther’s writings then can modeled as shifting preferences. But in my view is this doesn’t fully capture the role of an individual like Martin Luther in the seismic series of events we call the Reformation.

To understand the impact of Luther we also have to think about his role in coordinating opposition to the religious establishment. Luther was an important theologian, but he wasn’t just a theologian. He was an intellectual entrepreneur and a politically savvy operator.

Luther’s Network and its Role in Coordinating the Reformation

Fortunately to understand (2), we can rely on published research by Sascha Becker, Yuan Hsiao, Steven Pfaff, and Jared Rubin (co-author of How the World Became Rich). In a paper published in the American Sociological Review in 2020, Becker, Hsiao, Pfaff and Rubin (BHPR) studied the role Luther played in diffusing his ideas through his personal network.

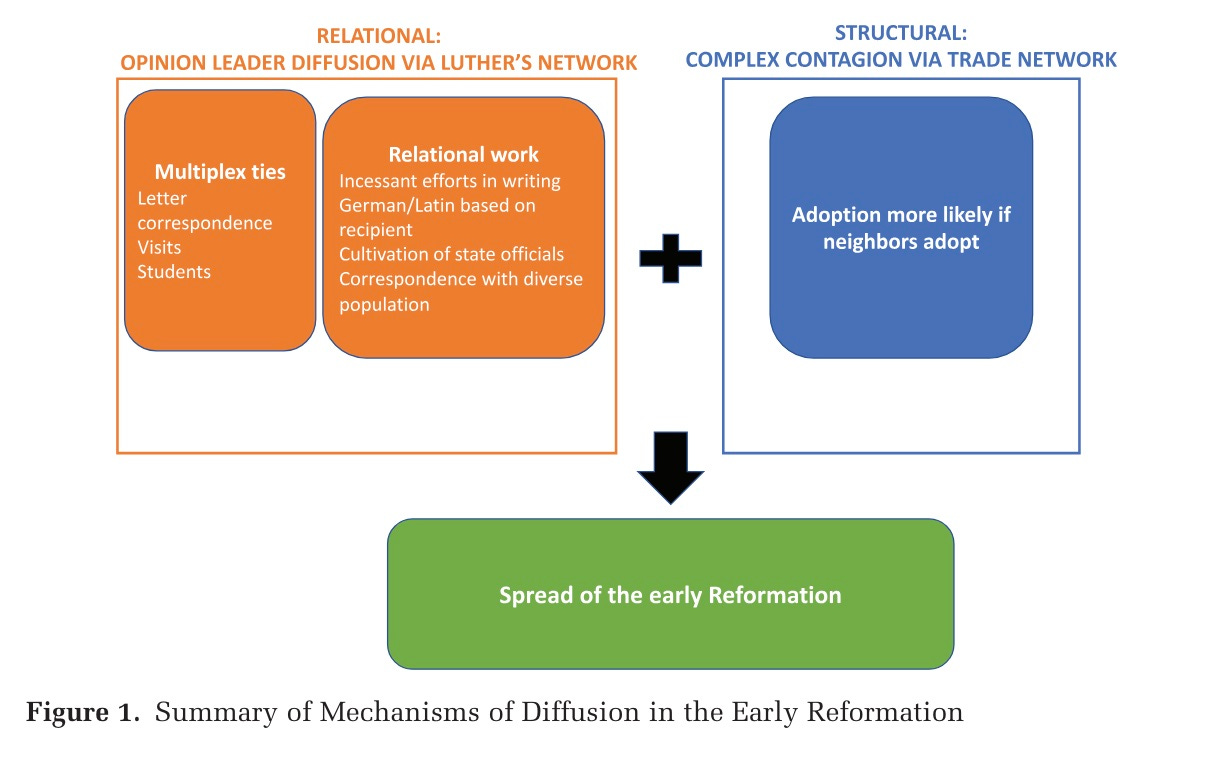

While the role of printing in spreading the Reformation is well known, BHPR argue that Luther’s personal network, specifically his letters and personal visits also played a critical role. They describe him as a “special kind of opinion leader, a “hyper-influential” person who could sway many people through persuasion and example” (Becker et al. 2020, p. 860). They formulate this hypothesis in Figure 1 below.

The authors find that cities Luther had personally influenced between 1517-1522 in the form of letters, visits or students were more likely to become Protestant by 1530. Similarly, the more personal influence Luther had on a city between 1517-1522, the more likely that it adopted Protestantism. This is clear simply looking at the bivariate relationships below.

Of course, in the paper the authors verify that this pattern holds up when using regression analysis and controlling for a host of other factors that also influenced adoption of the Reformation. If you don’t know the paper, I suggest checking it out.

Back to the role of individuals in economic history. The above analysis offers a way to think about decisive individuals in history.

Was Churchill decisive in 1940? Many historians say, yes. Was Luther decisive in 1517-1522? Also yes, in the following sense. While the dry tinder was already there and while there were many radicals dissatisfied with aspects of the medieval Church, it is hard to envision any of them lighting the conflagration that Luther did.

Other radical theologians might have gained either a scholarly audience or a popular one. Part of Luther’s distinctive contribution was his ability to influence both elites and the broader, literate, public across Germany-speaking Europe.2

Coordination Games versus Prisoner’s Dilemmas

What this analysis suggests is that individuals can be decisive for understanding institutional change if they coordinate other individuals.

In cases where there is only one possible long-run equilibrium, this role is irrelevant. For example, let us grant that serfdom was in terminal decline in England by around 1400. The increased value of labor meant that ending serfdom was the only feasible equilibria. In this case, the role of any one individual would be limited: serfdom would end either way.

But if there are multiple feasible equilibria, certain individuals can have an outsized impact. They can enable societies to coordinate on specific outcomes/institutional arrangements.

Another way of saying this, is that if the situation a society faces resembles a Prisoner’s Dilemma, then the role of any one individual is limited. But if the situation is, instead, a coordination game (like Battle of the Sexes), then certain individuals can really matter.

And thanks to the anonymous referee who pushed us on this point!)

Critical to Luther’s success was his impact on Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony. Frederick was Pope Leo X’s proposed "anti-Habsburg” candidate for Holy Roman Emperor. And he was famous as a collector of relics. But when Luther was charged with heresy, Frederick protected him. Perhaps he was the decisive individual?

Excellent stuff Mark. I’ve written about this myself https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2265111