The Political Power of Civil Society

Or why protests alone usually don't bring down autocratic regimes

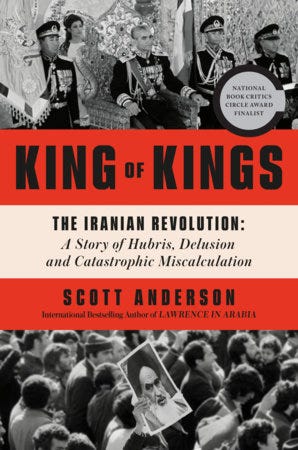

As the protests and subsequent bloody repression in Iran were unfolding in January 2026, I was immersed learning about the Iran Revolution of 1979 by listening to audiobooks and The Rest is History’s podcast series.1 I was also doing the proofs for a paper with Desiree entitled The Power of Civil Society, now out in the Journal of Comparative Economics.

Our paper asks: under what circumstances do protests bring down an autocratic regime? We don’t know the medium or long-run consequences of the December-January protests in Iran, which began as protests against soaring inflation, a collapsing rial, and economic mismanagement but coalesced into demands for full regime change. But we do know that the initial momentum of the protests appears over and that for now what appears to have been an incredibly brutal repression has pacified the country.

This illustrates a common phenomenon. Western observers and journalists routinely overestimate the ability of protests to bring down autocratic regimes. Brought up with images of the Fall of the Berlin Wall or the Color Revolutions in Eastern Europe, we seem to imagine that such protests have the force of history behind them and are destined to succeed. Social scientific research, in contrast, documents that successful regime changes are usually internal coups and typically rely on powerful regime insiders defecting.

Why do we overestimate the power of protests? Part of this is translating the logic of protests from democratic regimes to autocracies. Even in democracies, I suspect protests are overrated. The Iraq War Protests in Britain didn’t stop the war or prevent the subsequent reelection of Tony Blair in 2005. Peaceful protest is an important democratic right. So we tend to romanticize it and overestimate its power.

The Death of Stalin is much better social science than V for Vendetta.

Nonetheless, there is a logic of political protest and a cost that protests can impose even in autocracies. Furthermore, we uncover the role that cross-cutting ties between ordinary people and political elites play in amplifying these costs. In so doing, we can shed light upon the role that civil society can play in driving political transitions.

Here is how we think about it. Consider the influential selectorate theory developed by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and his collaborators. All rulers, whether democratic or autocratic, need the support of some coalition to stay in power. Call the “selectorate” the pool of people who have some say in choosing leaders. Then there is a ruling coalition, which is the smaller group whose active support is essential for survival.

Leaders maintain power by distributing a mix of public goods (which benefit everyone) and private transfers or patronage (which benefit only coalition members). In democracies, winning coalitions are large, so leaders must rely more on public goods provision; in autocracies, coalitions are small, so leaders can buy loyalty through targeted patronage. This framework offers a unified way to think about political survival and governance.

What our approach adds to selectorate theory is a focus on civil society and the role of ordinary citizens who fall outside the winning coalition. Traditional selectorate models focus on how leaders maintain elite loyalty, but largely ignore the ordinary citizens who cannot directly remove the ruler. We show that these ordinary citizens still matter indirectly because they can protest. In our telling, protests don’t directly topple a dictatorship — after all, who has the guns? But protests raise governance costs and therefore they can be decisive if they induce political actors to defect.

Civil society organizations, be they parties, NGOs, trade unions, or social clubs, can matter here if they are groupings that span both political actors and ordinary citizens.

Our model then distinguishes between those elites who can remove a ruler from power directly (we call them political actors) and ordinary citizens who cannot directly depose a ruler. Ordinary citizens can protest. But protests don’t automatically lead to regime change. Rather, they simply make it harder for a ruler to maintain loyalty among political actors, but protests alone are rarely sufficient.

This allows us to articulate a novel role for civil society organizations even in autocratic regimes. Our main result is that civil society organizations that include both political actors and ordinary citizens are far more effective at achieving political change than organizations composed of only one type.

An organization of only ordinary citizens can protest, but a well-resourced ruler can weather the storm. An organization of only political actors can threaten defection, but without popular support, they’re easier to buy off with patronage.

But a cross-cutting organization that spans both types creates a powerful feedback loop: popular discontent among ordinary members puts pressure on political actor members, who can then credibly threaten to withdraw support from the regime.

In the paper, our key example is historical: the Glorious Revolution of 1688. But we also discuss some other case studies and it is those I’ll focus on here.

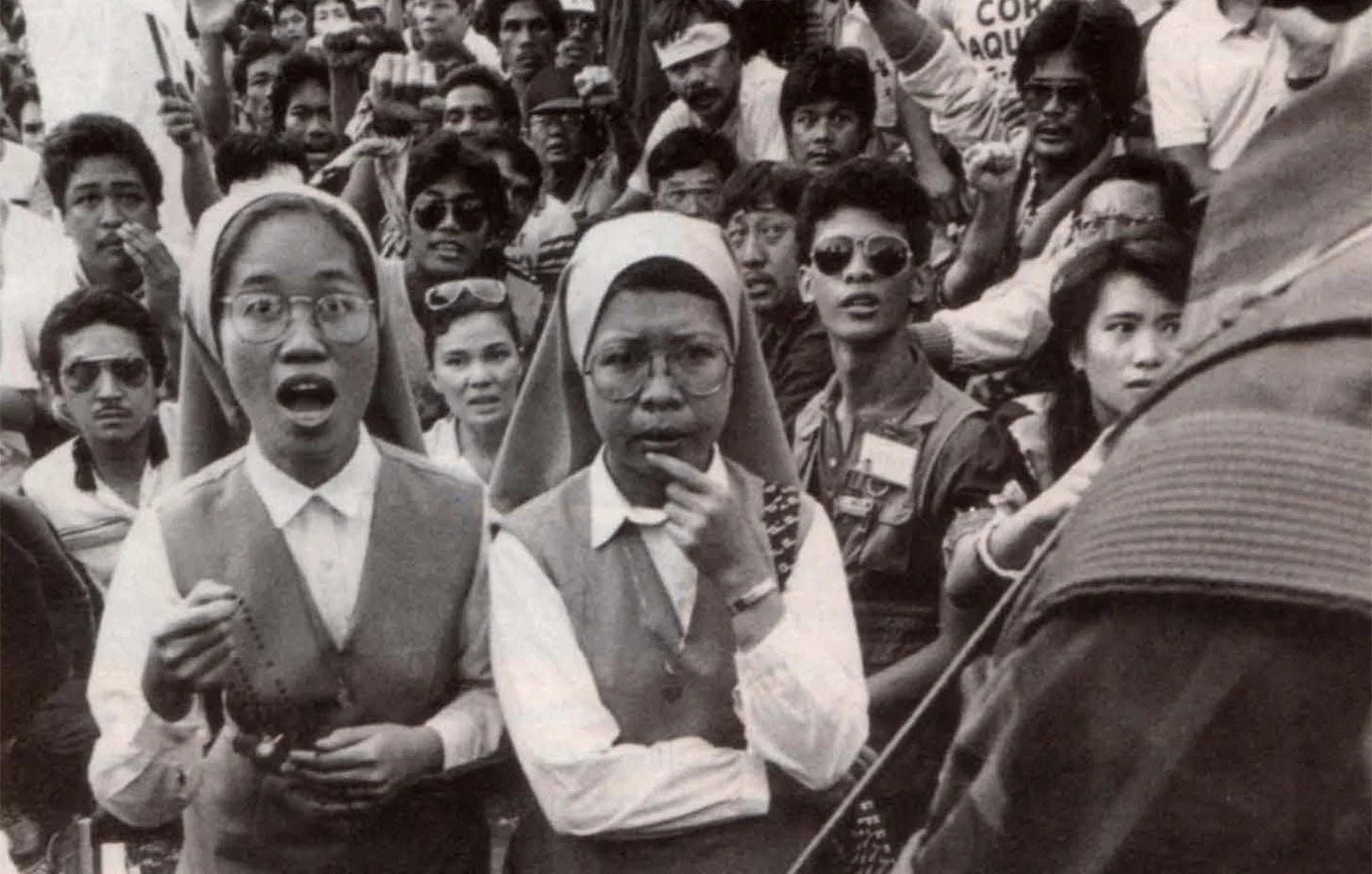

The People Power Revolution

In 1986, President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines was deposed peacefully as a result of popular protests. Why did popular pressure work in this instance but not in others?

While there are many reasons for this, our model provides an analytical template for understanding why Marcos was unable to hold on to power in the face of the People Power movement. As we discuss in the paper:

“Marcos had been in power since 1965 and had declared martial law in 1972, which allowed him to rule as a dictator. By the early 1980s, many segments of Philippine society, elites as well as the masses, had reasons to oppose his continued rule. His regime was characterized by widespread corruption — a ‘politics of plunder’ — and human rights abuses.”

At the same time, Marcos’s regime was far from totalitarian. There was widespread support for more democracy, and civil society organizations were allowed to flourish. The economy was also heavily reliant on American investment.

External economic pressures and the cutting of international lending created the situation that made Marcos vulnerable. Various organizations, including labor unions, student groups, and professional associations, mobilized the public against the Marcos government.

The most important civil society organization, however, was the Catholic Church. Initially, Church leadership in the Philippines was willing to support Marcos because he was anti-Communist. But after the murder of opposition leader Ninoy Aquino, their position changed and Church leaders like Cardinal Sin called for a democratic transition.

What followed in early 1986 was a classic example of popular protest inducing regime change. Protests involving priests as well as pro-democracy activists jammed up the main roads bringing Manila to a standstill. This dramatically raised the costs of repression to the Marcos regime (killing Communists in secret was one thing, shooting priests and nuns in public would be quite another).

In the language of our model, these protests raised the costs facing the government and dramatically increased the costs and risks of repression (as international attention was now focused on the ongoing revolution). From the perspective of our model, this, in conjunction with the drying up of external loans and US support, made it very difficult to buy off members of the ruling coalition. Key military and government officials, including Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Armed Forces Vice Chief of Staff Fidel Ramos, then defected from the Marcos government and declared their support for the opposition leader Corazon Aquino. By February 26, Marcos realized that he could not govern and resigned and went into exile.

As we argue in the paper, the example of the People Power Revolution illustrates the usefulness of our model in understanding regime change. The Catholic Church’s role in organizing opposition to Marcos was critical because it was a wide-reaching group spanning both political actors and ordinary citizens.

There are of course clear parallels to the role Solidarity played in Poland at the same time. At the same time, this example illustrates why popular protests elsewhere have failed to bring down autocratic regimes.

The Arab Spring

An important counterpoint is the Arab Spring. As is well known, the initial spark was the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi on December 16, 2010, in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid. Protests against President Ben Ali then spread across Tunisia, and then to Egypt where protesters opposed the regime of Hosni Mubarak, and from Egypt across the Middle East.

The Arab Spring was a dramatic series of events that grabbed world attention. But it did not deliver on its promise to spread democracy across the region.

Many scholars have offered assessments for this failure. From a Marxist perspective, the Arab Spring failed because it was a revolution without revolutionaries. But many scholars argue that what limited the effectiveness of the Arab Spring were the divisions among the various dissident groups. At the time, my colleague Jack Goldstone warned that “history is replete with student movements, workers’ strikes, and peasant uprisings that were readily put down because they remained a revolt of one group, rather than of broad coalitions”.

We draw on this assessment to argue that the long-standing weakness of civil society organizations in the Middle East meant that there was an absence of genuine cross-cutting groups.

As such, in contrast to the Philippine case, the Arab Spring did not involve organizations which spanned all of society. In addition, many rulers in the Middle East have greater resources to quell opposition. On the eve of the Arab Spring, countries like UAE, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia had access to substantial oil revenues, which, according to our model, would make their regimes more resistant to popular pressure. Interestingly, it was only in Tunisia where there had been a strong labor movement (the Tunisian General Labour Union, the UGTT) that the regime fell and was not reimposed.

I highly recommend James Clavell’s epic novel Whirlwind, published in 1986.