Thoughts on the Mirror and the Light and the Tudor Revolution in Government

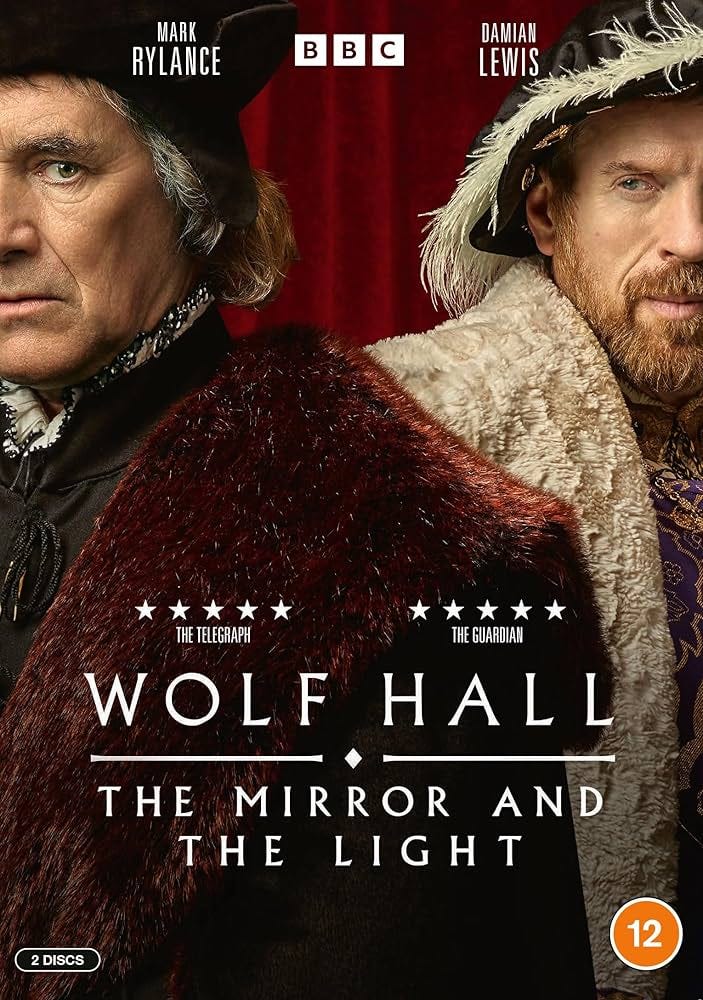

I've just finished watching the second season of Wolf Hall, The Mirror and the Light, adapted from Hillary Mantel's 2020 novel of the same name. The sets, costumes, and acting are marvelous and in keeping with the high standards set by season 1. Nonetheless, as a treatment of Cromwell and his historical role, it didn't live up to my expectations. It wasn't quite the show I wanted it to be.

This post will mostly be about why, and why Thomas Cromwell matters for thinking about some of the big questions in economic history.

But first a detour about the limits of TV as a medium for understanding history.

In recent years, commentators have, I think, come to the belated realization that the "age of prestige TV" was less of a golden age than we imagined. While there have been some exceptions (like the first season of Wolf Hall), most TV series produced since 2011 (when Game of Thrones premiered) will be soon forgotten. This is especially so of many of the historical TV series. The Medici, anyone? Or Versailles?1

Why is this? One failing is that geopolitics, economics, religion and strategy are not investigated in detail. When they are depicted, they are flattened into personal antagonisms. Personal conflict and romance are easier to depict.

Despite the quality of the production, I worried that The Mirror and the Light risked falling into this trap. Too much screen time was devoted to humanizing Cromwell.

The antihero who commits terrible crimes but also loves and wishes to be worthy of love is a mainstay of modern fiction – think Tony Soprano. And Mantel's portrait of a protean, aspiring, ambitious, but also human and humane, Cromwell was a revelation. Here, we see him try his best to look after a series of vulnerable young women: Princess Mary, Queen Jane Seymour, the illegitimate daughter of Cardinal Wolsey, and his own daughter. The quality of Mark Rylance and the other actors make many of these scenes compelling. But each scene is a variation on the same theme. Dramatically, these scenes may be needed; but narratively they are constraining and restrict the scope of the historic drama being depicted.

By episode 6, I was almost won around. Cromwell's rapid fall from power is brilliantly depicted. The fragility and arbitrary nature of political power at the top of the pyramid is exposed. Cromwell's mistakes don't have to be particularly momentous for Henry to tire of him and for his enemies, principally the Duke of Norfolk, to sweep in. Nonetheless, everything happens so fast. I would have appreciated more than one episode where we got to see more about why the likes of Richard Rich and Thomas Wriothesley choose to betray their master (see below).

I wish more TV shows as ambitious as Wolf Hall were being made. In this essay, though, I want to delve into some more problems with how Cromwell is depicted both in the show and in the novels.

[Note there are spoilers below for Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light]

The Problem of Thomas Cromwell

The Mirror and the Light both as a TV show and the novel face the same dilemma: How to explain the fall from power of a man who up until this point has been shown to be an incredibly capable administrator and courtier, the man who always knows what to say and how to say it.

Mantel, in the novel, explores Cromwell's unraveling through his rivalry with Thomas More. She invents a backstory between them: Cromwell had been a servant at More's school and had looked up to More; but More has no memory of it and never recognizes Cromwell's worth. Peter Straughton and Peter Kosminsky, the writer and director of the TV series, cannot do this because their depiction of More – played by Anton Lesser – was less nuanced than in the book itself, emphasizing his priggishness and hypocrisy, without granting him any of his historical grandeur. And Mantel's portrayal of More was already controversial.2

The show replaces More's role in Cromwell's interior dialogues with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the father figure and mentor who plucked him from obscurity. Instead of being haunted by his role in More's death, he is obsessed with the idea that in his rise to power he may have betrayed his patron. Ultimately, however, this can't bear the dramatic weight it's supposed to; it cannot adequately explain Cromwell's own personal dissolution. Given Cromwell's abilities, it is unclear why he felt he owed so much to the Cardinal. Moreover, if Cromwell's Protestantism is as sincere as recent historians and Mantel believe, then why does Cromwell have such fealty to the corrupt embodiment of the old church?

But to explain why Wolf Hall but especially The Mirror and the Light felt like a missed opportunity, one needs to delve into the political economy of Tudor England.

Missed Opportunity 1: Cromwell's Boys

Wolf Hall captures the sense that Tudor England was a highly fluid and meritocratic society. Indeed, those depicted in the show as "old aristocracy" were in fact relative parvenus. The Duke of Norfolk makes much of Cromwell's lowborn status. But in reality, Thomas Howard's family had only been recently ennobled as a result of the extinction of the Mowbray line. The Howard family had been prosperous gentry until the late 15th century. The Tudors themselves of course were Welsh outsiders.

Amid this flux, Cromwell stands out as someone who can pick out talent and ambition. He collects ambitious young men; men who then rise alongside him.

Having lost his daughters, among the young men he raises is Ralph Sadler who remains loyal to Cromwell even to the end (and would rise to become a privy counselor under Elizabeth). Cromwell treats Sadler as a son. One of his endearing characteristics is his sense of family duty. His ambition is partly in the service of establishing his family and those who have served him well.

So, who else does he support and reward? And what does his selection reveal about his character and goals?

Apart from Sadler, two others stand out among Cromwell's coterie: Richard Rich and Thomas Wriothesley. And in the final episode they are prominent in his fall. Wriothesley, in particular, incriminates his former master. But his betrayal seems reluctant. It is intended to indict the overall political environment rather than the man. The court of Henry VIII is, as we know, a dangerous and ruthless place.

But Straughton and Kosminsky missed a trick. Rich and Wriothesley are among the most repellent and scheming individuals in Tudor history. They are most notorious for personally racking Anne Askew in the Tower of London until her limbs were pulled from their sockets. Rich was a political survivor. A man who rose to prominence by testifying against More in his trial and became "rich" acquiring large amounts of monastic lands during the Dissolution, but who during Mary's reign was a leading persecutor of Protestants in Essex. He remained in favor during Elizabeth's reign, changing his religion and politics to suit the times: a man who has been described as the “arch-villain of Tudor history.”3

Mantel knew about how unscrupulous and shady Rich and Wriothesley are. But it seems like the screenwriters and the actors in the Mirror and the Light apparently don't, so their portrayal was underwhelming. It is not simply that they are men corrupted by the system; rather they are further evidence for F.A. Hayek’s thesis about authoritarian or totalitarian government — that the “worst get on top’’ i.e. that there is a process of negative selection.4

Missed Opportunity 2: What Happens to the Poles?

The Poles and the Courtenays represent the remnant of the old medieval nobility of England, many of whom had been wiped out by the Wars of the Roses or reduced in prominence by the fiscal policies of Henry VII.

There were three Pole brothers, rough contemporaries of Henry VIII: Henry, Geoffrey and Reginald. They were rich, powerful and politically prominent; they possessed Plantagenet blood via their mother Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, and owned lands across England. They had not been in favor of Henry's divorce, and all had traditional religious sympathies.

A decisive break occurred when the youngest Pole, Reginald, who had been in semi-exile, denounced Henry’s break with Rome and urged his deposition. As Henry's government reacted to the aftermath of the Pilgrimage of Grace, Cromwell used this as an opportunity to eliminate the Pole family and their allies. These included Henry Courtenay, a cousin of Henry VIII and a descendant of the House of York, and Edward Neville, a member of the great northern family that had played so prominent a role in the Wars of the Roses.

The Mirror and the Light shows us some of this in Episode 3 but then entirely drops this plot point. We see Cromwell intimidating Geoffrey Pole, but we aren't told that the rest of his family (bar Reginald) are wiped out. Margaret Pole’s horribly botched execution admittedly happened after Cromwell’s death. But leaving the fate of the Poles unspecified is itself a problem. The TV show's relentless focus on Cromwell's fate obscures that of his victims. This is a missed opportunity. Cromwell's ruthless destruction of the Pole family and men like Henry Courtenay, who had been bosom companions of the King, presages the vicious way Henry and the other courtiers will turn on Cromwell in 1540 and reveals the dark side of his state-building project.

Missed Opportunity 3: The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Pilgrimage of Grace

Having just written a paper (with Desiree Desierto and Marcus Shera on the dissolution of the monasteries), I naturally think that The Mirror and the Light doesn’t spend nearly as much time as on this it should!

England’s monasteries were incredibly rich and owned vast swathes of land. The dissolution of the monasteries between 1536 and 1540 was a huge event which had consequences that would reverberate for decades if not centuries. In his recent account, The Dissolution of the Monasteries, James Clark writes that:

“As a shockwave shared countrywide, it recalled only moments in the remote past, the Black Death, nearly 200 years distant, or the conquest of the Normans another three centuries beyond that”.5

In contrast, the Dissolution is just part of the background in The Mirror and the Light. The scale of the disruption is not shown and Cromwell’s part in this revolutionary episode is consequently under-explored.

When Cromwell visits Shaftesbury Abbey in Episode 2, he reassures the Abbess that the Dissolution will not effect her. It is, he says, only about closing the smaller monasteries, eliminating waste and corruption, and reallocating resources. Is he lying? Or is he telling the truth?

We are not told. But this is a weighty question. Did Cromwell plan on eliminating all of England’s monasteries as early as 1536? Or was the policy much more ad hoc, driven by opportunism and other actors? Clark notes that recent research has “questioned Cromwell’s capacity to orchestrate policy as well as he could conceive its central theme,” and suggests that “it was the servants of this vast undertaking, and not its master, who first perceived its problems and proposed its solutions.”6 To what extent was he driving Henry’s policies and to what extent was he riding a tiger?

Mantel’s portrayal of Cromwell does not resolve this tension.

Similarly, the audience was underserved by not being shown the political reaction to the Dissolution. The rebellions in the north of England against Henry and Cromwell’s policies occur offscreen. Cromwell stayed in London while the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion was taking place and The Mirror and the Light almost exclusively follows Cromwell (though we occasionally have scenes without him).

We never see the popular unrest and we don't see Henry's duplicitous offer to negotiate with the rebel leader Robert Aske or his hosting of Aske at court during Christmas 1536, all events that Cromwell would have been involved with. And we don't see the subsequent repression.

And the repression was brutal. The Duke of Norfolk declared martial law so that he could executed rebels en masse without recourse to jury trials (as he expected many of them to be acquitted by their neighbors). Cromwell was responsible for interrogating Aske personally and for constructing the (legally dubious) case against him.7 Aske and hundreds (!) of other rebels were executed by being hanged in chains.

This apparently involved being hanged alive in chains until one died, a form of death that could take days.8

This brings me to some concluding thoughts. How should we think about the process of state-building and the often brutal and ruthless ways in which modern states were constructed.

Cromwell and the Modern State

In both her Cromwell books and in her excellent novel of the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety, Mantel's sympathies are with those individuals who, by disrupting the old moribund and irrational order of things, are responsible for bringing the modern world into being.

Cromwell in her novels is such an avatar of modernity. He embodies all the apparently "new" things that historians identify with the post-1500 order. His rise is based on merit and ability; he has no noble ancestors; he is comfortable with commerce and nascent capitalism, as well as with the law; he despises superstition and traditional Catholic religiosity, and though a sincere bible-reading follower of Tyndale, in practice, he is a vehicle of secularization and the privatization of religious faith. Above all else, he is associated with the rise of a stronger and more assertive state. He was building state capacity.

This Cromwell owes much to Geoffrey Elton's classic The Tudor Revolution in Government. Elton was perhaps the first historian to depart from the traditional depiction of Cromwell as a schemer who sought to make Henry an absolute monarch. Rather he emphasized that "the Henrician Reformation rested on conscious co-operation with Parliament and that the propagandists of the time never produced a theory of absolute monarchy". Elton argued that Cromwell was not only a master of bureaucracy but also that his "political creed centred on the legal supremacy of the king in Parliament and included no ambitions for a purely royal despotism".9 Subsequent scholarship has modified many of Elton’s claims but his portrait of Cromwell has largely survived.10

In his excellent Thomas Cromwell: Machiavellian Statecraft and the English Reformation, J. Patrick Coby lists Cromwell’s praiseworthy traits: he could be charming and warm, his intellectual interests ranged widely, he enjoyed entertaining at dinner etc. in a manner that is entirely consistent with the rich and nuanced portrait of Cromwell we get from The Mirror and the Light. But he follows this with:

“. . . But he could be terrifying . . ."11

Like the French Revolution then, where one stands on Cromwell sheds interesting light on one’s broader ideological commitments. It is revealing that Simon Schama was a notable critic of Wolf Hall’s depiction of Cromwell, saying:

“ . . . the documents shouted to high heaven that Thomas Cromwell was, in fact, a detestably self-serving, bullying monster, who perfected state terror in England, cooked the evidence, and extracted confessions by torture.”12

Schama is not a Tudor specialist (and in blaming Cromwell he may be inadvertently letting Henry VIII off the hook) but he is the author of a landmark history of the French Revolution, Citizens which is notable for its emphasis on its human cost. In other words, Schama is more attuned to the human costs of state-building than are either Elton or Mantel.

My feeling after reading and watching Mantel’s Cromwell are that, excellent though both the television show and the books are, they provide only a partial window into Cromwell’s role in the turbulent mid-16th century period of Reformation and state-building. I’m still holding out for a television show or a film capable of showing us this.

The really memorable and innovative shows predate the prestige TV-era; the Sopranos, the Wire and HBO's Rome are at least 20 years old. The Wire contains genuine insights into how organizations function and why reform is so hard.

Mantel clearly wanted to replace the pristine image of More from A Man of All Seasons. But as Eamon Duffy discusses, she has no feel for More's passionate and sincere religious faith. See Eamon Duffy. 2017 Reformation divided: Catholics, protestants and the conversion of England. Bloomsbury Publishing, Chapter 1.

Rich is of course a major villain in C.J. Sansom’s Shardlake series.

See Chapter 10 of The Road to Serfdom. Here is a free version: https://fee.org/resources/the-road-to-serfdom-chapter-10-why-the-worst-get-on-top/.

James Clark. 2021. Rhe Dissolution of the Monasteries, Yale University Press, p 8.

Clark. Page 17.

Legally dubious because Aske had already received a royal pardon for his rebellion. His conviction relied on a letter he wrote asking his followers not to join the Bigod Rebellion of 1537. He was convicted of treason on the basis that his letter did not urge them to join the King’s army raised to suppress the rebellion.

C.J. Sansom has a good account of how horrific this was in Sovereign. I also found this youtube video informative and very disturbing.

It is interesting to note that this argument finds favor with recent political economy accounts by economic historians that emphasize the extent to which Henry VIII relied on parliamentary support to carry out his policies. Greif and Rubin have recently argued that

“Beginning in the 1530s, Henry VIII fostered the legitimating power of Parliament by regularly and publicly declaring that acts were issued by the authority of Parliament and not by his authority. An act was now declared, in Henry’s words, “by the King’s most excellent majesty, with the advice and assent of the Lords spiritual and temporal, and the Commons, in the present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same” (Elton 1974b, p. 30). This formula explicitly recognized that a law was enacted by the crown in Parliament, requiring the consent of the Commons, Lords, and the crown. Subsequent Tudors continued doing so, and this enactment formula has become standard ever since.

In other words, the Tudors increased the legitimating power of Parliament by publicly changing the legislation process from one in which the crown legislated in consultation with the Lords and the Commons (crown and Parliament) to one in which Parliament legislated by the consent of the Lords and Commons, with the assent of the crown (crown in Parliament).”

See Avner Greif and Jared Rubin, 2024 Endogenous Political Legitimacy: The Tudor Roots of England’s Constitutional Governance. The Journal of Economic History. (3):655-689.

Perhaps the best evidence of Cromwell’s competence and abilities comes from what happened after his execution. As Anton Howes discusses in the fascinating Works in Progress podcast, in the 1540s following Cromwell’s fall, Henry VIII pursued a series of disastrous policies that nearly brought England to the brink of collapse.

J. Patrick Coby. 2009. Thomas Cromwell: Machiavellian Statecraft and the English Reformation. Lexington Books, p 194.

I was disappointed with the second season too (and I wrote a review for it on my 'stack). The biggest problem is it seems they made it for people who've read the books and can fill in the gaps of the story. And by not showing more of that story, it's not very easy for casual viewers to understand what's happening. Looks great, but could've been so much better.

Super article. Thank you for sharing.